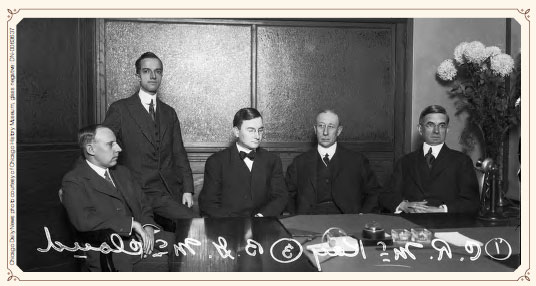

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke (center) with (left to right) Board of Directors Deputy Chairman Gregory Q. Brown, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Schaumburg, Ill.-based Motorola Solutions, Inc.; Board of Directors Chairman Jeffrey A. Joerres, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Milwaukee-based ManpowerGroup; Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Charles L. Evans, and Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago First Vice President Gordon Werkema.

At the end of 2013, we celebrated the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Federal Reserve Act. In addition to that, a second important anniversary arrives this year – the centennial on November 16 of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s first day of operation. In recognition of these anniversaries, this annual report is titled “A Century of Service” and features a photo essay of nostalgic bank images.

It’s hard to look at these photos and not think about how much has changed over the years. Our hope, however, is that you will also discover how much remains the same: our sense of purpose, our commitment to a strong and stable economy and payment system, and our dedication to public service. This is a legacy forged over the last 100 years.

The people who have created that legacy are our very talented staff members, both past and present. I salute them for their efforts over the years. Also important are the contributions of our past and present directors, whose guidance has been invaluable.

I would especially like to recognize the directors who left our boards at the end of 2013. One is Detroit board member Carl T. Camden, president and chief executive officer of Kelly Services, Inc., in Troy, Michigan, whose service included two years as chairman. The other is Mark Hewitt, president and chief executive officer of Clear Lake Bank & Trust Company in Clear Lake, Iowa. I would also be remiss if I did not mention the departure earlier this year of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke. Ben contributed greatly during his many years of service. His experience and intellect will be missed. I firmly believe he was the right person in the right job at the right time to direct our response to the Financial Crisis. Fortunately, we are in excellent hands with our new chair, Janet Yellen. She also brings a wide range of experience and knowledge to the position, and I look forward to continuing to work with her.

In addition to the photo essay in this report, you will find an excerpt from a speech I gave recently about how as a policymaker I approach the juxtaposition of our monetary policy and financial stability objectives. I hope you find this information useful and interesting as we start a new “century of service” promoting a strong and stable economy.

Charles L. Evans

President and Chief Executive Officer

April 1, 2014

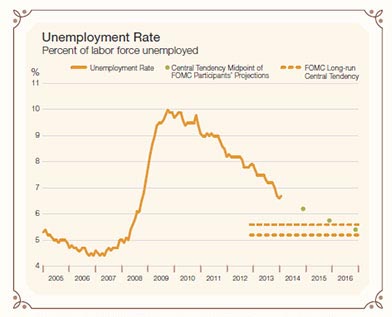

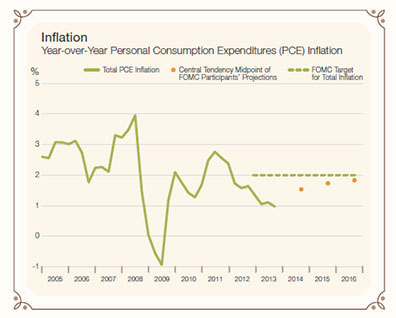

The U.S. economy grew moderately over 2013 as a whole. Real gross domestic product (GDP) rose 2.6 percent, up from a 2 percent increase in 2012. The unemployment rate fell about 1 percentage point; still, at 6.7 percent, the rate in early 2014 remains above its longer-run normal level. Inflation was significantly below the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) target of 2 percent for all of 2013, with the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index ending the year 1 percent higher than at the end of 2012 and core PCE inflation (excluding volatile food and energy prices) up 1.2 percent.

With the improvement in labor markets, the FOMC reduced the pace at which it is buying long-term mortgage-backed and Treasury securities in its large-scale asset purchase program at its December 2013 and January and March 2014 meetings. Nonetheless, with labor markets still not fully recovered from the recession and inflation running significantly below its target, the FOMC has stated that it anticipates highly accommodative monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after its asset purchase program ends.

A major component of this policy continues to be the forward guidance provided by the Committee on future federal funds rates. The FOMC has stated that it will take a balanced approach in determining appropriate policy consistent with its longer-run goals of maximum employment and inflation of 2 percent and consider a wide range of information in its assessment of progress toward its objectives, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial developments. According to the median expectation of the FOMC members, the first increase in the federal funds rate is not likely to occur until sometime in 2015.

Based on FOMC participants’ assessments of appropriate policy, the central tendency midpoint of the FOMC forecasts made in March 2014 looked for real GDP growth to pick up to around 3 percent over the 2014-16 period. The unemployment rate is projected to trend down further, coming within range of its longer-run normal level by the end of 2016. The FOMC also projected that inflation would move up, coming close to its target of 2 percent in 2016.

As of the March 18-19, 2014 meeting, the FOMC expected that the unem- ployment rate will trend down to a range consistent with the maximum employment mandate of the Fed by 2016.

Source: Haver Analytics and the Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee

The Economy

The U.S. economy began 2013 sluggishly. However, an encouraging acceleration in activity took place in the second half of the year. While some of the increase can be attributed to transitory inventory investment, final demand also increased, led by net exports and personal consumption expenditures. Household balance sheets benefited from rising equity and home prices in 2013; and demand for durable goods remained strong, with the pace of light vehicle sales reaching its highest level since 2007. Expenditures on nondurable goods and services also increased in the latter half of the year. Residential investment grew at a healthy rate over the first three quarters of 2013, but fell later in the year as higher mortgage rates dampened activity.

Declining federal government purchases restrained growth throughout the year, reducing real GDP growth by half a percentage point in 2013. Business investment was soft early on, but picked up later in the year. For 2013 as a whole, investment in equipment and intellectual property grew at about the same moderate pace as in 2012, while investment in structures contracted slightly.

The labor market continued to show steady improvement, as total nonfarm payroll gains averaged 194,000 per month in 2013, up from 186,000 in 2012. However, payrolls are still below their cyclical peak reached in January 2008. Long-term unemployment also remains elevated, and labor force attachment continued its long-running decline in 2013, with the labor force participation rate falling eight-tenths of a percentage point over the year.

As of the March 18-19, 2014 meeting, the FOMC expected inflation to be below 2 percent in the near term, rising toward its mandate-consistent level by 2016.

Source: Haver Analytics and the Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee.

Monetary Policy

With employment and inflation running persistently below their longer-run goals, the FOMC maintained an accommodative stance for policy in 2013. The federal funds rate was unchanged throughout the year, and the large-scale asset purchases initiated in late 2012 continued at a pace of $85 billion per month throughout 2013. However, in light of the substantial improvement in labor markets since the program began in 2012, the FOMC decided to reduce the pace of purchases by $10 billion per month at each of its December 2013 and January and March 2014 meetings.

With the unemployment rate nearing 6-1/2 percent, the Committee at its March 2014 meeting also updated its forward guidance regarding the timing of the first potential increase in the federal funds rate. The FOMC noted that it anticipated it will likely be appropriate continuing the current target range for the federal funds rate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends, especially if projected inflation remains below the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal and longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored. The Committee also indicated it currently anticipates that even when unemployment and inflation approach mandate-consistent levels, economic conditions likely will warrant keeping rates below their normal long-run levels for some time.

*Data current as of March 28, 2014.

Formulating Monetary Policy

- Participated in meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee, the group headed by Janet Yellen that formulates national monetary policy.

Conducting Economic Research

- Researched and analyzed important topics including national and regional economic policy, the dramatic decline in the labor force since 2008, the Fed’s role as a liquidity backstop provider, and the insurance and payments industries.

- Studied state and local government policies, including the impact of the city of Detroit’s bankruptcy filing on financial markets.

- Provided expertise on high-speed trading risk controls and electronic market infrastructure and analyzed the impact of insurance companies on financial stability.

Federal Reserve senior leaders take a moment to celebrate their victory in a team-building exercise at a professional development conference.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago commemorates 100 years of service with a window display of nostalgic photos.

Supervising and Regulating Banks

- Exceeded all supervisory mandates and expectations for timeliness in conducting examinations and delivering supervisory reports.

- Participated in implementation efforts surrounding recent supervisory guidance on the consolidated supervision of large financial institutions.

- Continued to house the Federal Reserve System’s Wholesale Credit Risk Center to support DFA capital stress testing requirements and monitor large financial institutions’ wholesale lending activities.

- Contributed to System efforts to implement supervisory programs required by DFA, such as savings and loan holding company oversight.

- Continued to promote the mission of the Financial Markets Utilities group, which works with primary regulators to advance supervision of these designated entities.

Providing Central Bank Services

- Selected to process the Capital Assessment and Stress Testing data and System Risk Report on behalf of the System.

- Worked with the Board and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to manage, monitor and create formal procedures for systemically important Financial Market Utilities.

Fostering Good Customer Relations and Support

- Met critical objectives, exceeded FedLine revenue targets, and completed the FedLine User Authentication Enhancement project, providing subscribers with a stronger security–authentication process.

- Led the System-wide efforts to gain feedback on the new Federal Reserve Financial Services strategic direction.

Fostering Community Development and Studying Policy

- Studied community and economic development issues, including trends affecting low- to moderate-income communities.

- Conducted a survey of Chicago small business intermediaries to better understand their perceptions of the economic and business climate, as well as surveyed Detroit small business owners about the importance of networks for obtaining financing, sharing information, and getting technical assistance and advice.

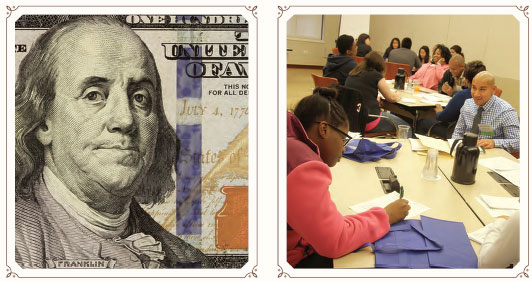

The new $100 bill, released on Oct. 8, 2013, incorporates state-of-the art security features that make it harder to counterfeit and easier to tell if it is real.

Ruben Trujillo (right) discusses money management and financial aid for college with Chicago high school students during a Money Smart Week event in April.

Carrying Out Currency Responsibilities

- Facilitated the release of the new $100 note and provided contingency storage to meet System-wide inventory needs.

Promoting Diversity and Inclusion

- Continued to provide key leadership to national diversity recruitment and national diversity supplier programs.

- Conducted diversity and inclusion training for all people leaders in the organization.

- Endorsed a Financial Services Industry pipeline initiative designed to increase the representation of Latinos and African-Americans in the financial services industry.

Fostering Partnerships

- Participated in or led numerous System-level committees and workgroups.

Other

- Achieved all operational goals and met budget targets by prioritizing initiatives and investments that maximized resources and operational efficiencies.

- Commemorated the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Federal Reserve Act.

- Continued to coordinate and grow Money Smart Week, with more than 3,200 free financial education classes offered in more than 35 states. Classes were attended by more than 134,000 consumer participants and hosted by partner organizations including financial institutions, universities, government agencies, community groups and libraries.

The following is an excerpt from a speech given by Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President and Chief Executive Officer Charles L. Evans to a gathering of the Detroit Economic Club on February 4, 2014.*

Charles L. Evans

President

It is easy and most natural for a Fed policymaker to talk about inflation. Price stability is one of the explicit goals of monetary policy as mandated by the U.S. Congress. Financial stability risks are more complicated. How does financial stability dovetail with the Fed’s dual mandate? There is clearly an interdependent relationship between them. A strong economy with low inflation provides a key stabilizing force for beneficial credit intermediation and robust financial market functioning. At the same time, stable and well-functioning financial markets are essential for achieving maximum employment and price stability. The global experience since 2008 reinforces this critical interplay between monetary and financial conditions.

However, beyond these basic principles, what is the appropriate monetary policy stance for achieving both financial stability and the dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability?

With inflation running well below our 2 percent longer-run target and the unemployment rate still well above its normal long-term level, appropriate monetary policy dictates that low real interest rates should prevail until the economy is further along a sustainable path to its potential level and inflation is closer to target. Nonetheless, it is common to hear the argument that these highly accommodative monetary policies might sow the seeds of financial instability.

The fear is that excessive and persistently low interest rates would lead to excessive risk-taking by some investors. For instance, some firms, such as life insurance companies and pension funds, are under pressure to meet a stream of fixed liabilities incurred when interest rates were higher.1 (And perhaps these liabilities were offered at somewhat generous terms to begin with.) To meet commitments like these in the current low interest rate environment, some firms have an incentive to reach for yield by investing in excessively risky assets. Furthermore, with the costs of borrowing at historically low levels, other investors might simply decide that this is a good time to cheaply amplify the risk and return in their portfolios by taking on more leverage.

One could reach the conclusion that historically low and stable interest rates pose a threat to financial stability. This creates a seeming paradox for policymakers. On the one hand, the existing large shortfalls in aggregate demand call for highly accommodative monetary policies and historically low interest rates. On the other hand, such policies have the potential to raise the likelihood of financial instability in the future.

So, the questions that I’m often asked regarding these matters are as follows: Do the regulators and the Fed have adequate safeguards in place to mitigate this potential financial risk? If not, should the FOMC step away from what we thought was the best monetary policy with respect to our dual mandate? Should we discard our nonconventional tools and raise the fed funds rate in order to reduce the possibility of undesirable financial imbalances in the future?

I don’t believe that such monetary policy adjustment is the right approach. I think the inference that persistently low interest rates pose a danger to financial stability is based on a narrow view of the economy. This narrow view is unlikely to survive a broader analysis that takes into account all the interactions between financial markets and real economic activity.

If more restrictive monetary policies were pursued to generate higher interest rates, they would likely result in higher unemployment and a sharp decline in asset prices, choking the moderate recovery. Such an adverse economic outcome is unlikely to set a favorable foundation for financial stability. Moreover, our short-term interest rate tools are too blunt to have a significant effect only on those pockets of the financial system that are most prone to inappropriate risk-taking. At the same time, these blunt tools could significantly damage other markets, as well as the growth prospects for the economy as a whole. Therefore, stepping away from otherwise appropriate monetary policy to address potential financial instability risks would degrade progress toward maximum employment and price stability. This approach would be a particularly poor choice when other tools are available, at lower social costs, to address the risk of financial instability.

Let me be clear. I am not saying that financial stability concerns are not relevant for the economy or that policymakers should not take decisive action against evelopments that threaten financial stability. Rather, I am saying that the macroprudential tools available to policymakers are better-suited safeguards to addressing financial risks directly. These macroprudential actions can be dialed up or down given the appropriate setting of monetary policy tools; so, undesirable macroeconomic outcomes are less likely than if we were to resort to premature monetary tightening. Indeed, any decision to instead rely on more-restrictive interest rate policies to achieve financial stability at the expense of poorer macroeconomic outcomes must pass a cost–benefit test. And such a test would have to clearly illustrate that the adverse economic outcomes from more-restrictive interest rate policies would be better and more acceptable to society than the outcomes that can be achieved by using enhanced supervisory tools alone to address financial stability risks. I have yet to see this argued convincingly.

Let’s discuss some of these macroprudential tools. One simple but important tool is enhanced monitoring. Even before the recent financial crisis, central bankers were well aware of the key role played by stable financial markets in economic activity. Since the crisis, however, the analysis of financial stability issues has been greatly expanded and given a more prominent role in the FOMC’s deliberations. We comb through reams of data looking for evidence of incipient risks to financial stability.

The Federal Reserve also has revamped its approach to bank supervision substantially to expand the focus on macrofinancial risks. Traditional bank supervisory tools are being used more intensively, and new tools have been developed. Bank capital stress tests are one well-known addition to our supervisory toolkit.

Another is the augmentation of traditional microprudential supervisory work that analyzes individual institutions with efforts that take a wide-angle view of the banking industry. Supervisors look to identify common trends across institutions and emerging concentrations of risks that might pose systemic threats to the financial system. This broad view also allows supervisors to better identify sound practices among firms and incorporate them into supervisory reviews and the feedback provided in them.

The Federal Reserve also has greatly expanded its surveillance efforts to financial markets outside of the traditional banking sector, such as the insurance industry and financial market utilities. These efforts are not confined to financial institutions per se, and reach a range of activities that might pose a potential threat to financial stability. For instance, staff members from the Chicago Fed are actively engaged in assessing the role of high-frequency computerized trading in securities and derivatives markets and associated risks that might arise with it.

These are just a few examples of regulatory tools available to monitor and promote financial stability. And there are a host of other instruments in our toolkit, such as resolution plans, liquidity requirements and single counterparty credit limits. All are examples of improvements in supervisory practices aimed at reducing the likelihood of systemic disruptions and containing the impact should such disruptions occur.

To reiterate, I currently expect that low inflation and still-high unemployment will mean that the short-term policy rate will remain near zero well into 2015. In this environment, some have questioned the ability of our supervisory and regulatory tools to adequately address potential financial instability risks. They argue that a broad tightening of interest rate policy might be more effective in catching incipient risks that might fall through the cracks. It is certainly true that higher interest rates would permeate the entire financial system. But this is just another way of saying that raising interest rates is a blunt tool. Higher interest rates would reduce risk-taking where it is excessive; but they also would result in a pullback in economic activity in sectors where risk-taking might already be overly restrained. That’s how a blunt tool works.

If you believe that financial stability can only be achieved through higher interest rates — interest rates that would do immediate damage to meeting our dual mandate goals at a time when unemployment is still unacceptably high — then we ought to at least ask ourselves if the financial system has become too big and too complex.

Think about how problematic the cost-benefit calculus becomes if the only way we can achieve financial stability is to raise interest rates above the level where the forces of demand and supply in the real economy put them. The possible benefit of such a restrictive rate move would be to reduce risks that might be forming in the nooks and crannies of a highly complex financial system. But the costs would be 1) higher unemployment; 2) a risk of choking off the economic recovery; 3) even lower inflation below our objective; and, somewhat paradoxically, 4) the introduction of new financial risks by reducing asset values and credit quality. Given such cost-benefit trade-offs, I would have to question whether the financial system has become too complex — perhaps complex enough to generate negative social value. Rather than degrading our macroeconomic performance through suboptimal monetary policies, I would have to consider whether we should contemplate big changes to the financial system — a lot more rules, substantially higher capital requirements for all institutions and maybe even fewer financial products.

However, I have a more favorable view of the social value of our financial system and the efficacy of supervision and regulation. Since the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve has expanded its macroprudential toolkit and enhanced its microprudential tools. We have also reoriented our approach to supervision to take full advantage of the Federal Reserve System’s wide-ranging expertise on macroeconomic and financial developments and risks.

I believe that these regulatory efforts can effectively minimize the risks of another crisis and increase the resiliency of the financial system. We can achieve these objectives without having to resort to wholesale changes to the financial system and without degrading our monetary policy goals. Maintaining the effectiveness of the financial system for generating more-robust economic growth continues to be a crucial objective for public policy.

1 I should note that increases in interest rates since last spring have increased discount factors and thus lowered the present value of pension fund and other fixed nominal liabilities. For instance, see Fitch Ratings, 2013, “Fitch: U.S. corporate pension plans underfunded status improves,” press release, New York,

August 15, available at https://www.fitchratings.com/web/en/dynamic/fitch-home.jsp.

*Text updated to reflect recent monetary policy developments.

By Gordon Werkema, First Vice President and Chief Operating Officer

Gordon Werkema, First Vice President and

Chief Operating Officer

This year marks our 100th anniversary of operating the nation’s payment system – one that touches nearly every depository institution in the country. In 1914 the newly established regional Reserve Banks started providing to member banks a national network of check-clearing services where checks would clear at face value. This improved what had been a complex and inefficient payment system, one operated mostly by private-sector parties. This national network formed the foundation for the work we do today.

For more than a century, the Fed has been fulfilling its mission to foster the integrity, efficiency and accessibility of the U.S. payments system. In this role, we act as both a service provider and a leader. We foster the evolution of the payments system by collaborating as a thought leader with industry participants and stakeholders. As we reflect on 100 years of service, what’s remarkable is not only the stability and ubiquity of a payment system that began a century ago, but also how time and time again we have addressed its evolving needs.

As an example, in the 1970s, when the number of paper checks grew so rapidly that concerns rose about whether volume might overwhelm processing capability, the Reserve Banks offered depository institutions the computer systems necessary to process routine payments electronically. What resulted was the automated clearing house (ACH), which today is the nation’s largest general purpose payment system.* Over the years, Reserve Banks have also collaborated with the industry to improve the efficiency of check collection. This started with improvements to speed up funds availability and then led to innovations such as the development of magnetic character ink recognition as well as high-speed processing equipment. The collaboration continued with what has probably been the most significant improvement to the payment system – the shift from paper check clearing to digital images. Check imaging has reduced processing costs dramatically for both Reserve Banks and depository institutions and has hastened the speed of collection time, to the dramatic benefit of end users.

Looking forward, the need to improve the payment system continues to confront us. Our task is to meet the challenges and opportunities of digital commerce. Traditional payment systems operate effectively and at low cost and may continue to be needed for certain types of payments. However, end users of payments are increasingly demanding real-time transactional and informational features with global commerce capabilities. The problem is that today’s payment system is not universally fast or efficient. At best, it currently takes a day to settle a payment made by check or ACH. In a society where many transactions are instantaneous, overnight clearing seems untenable. The challenge for the industry, and for us, is to provide a future payment system that combines the valued attributes of legacy systems with new technology enabling faster processing, enhanced convenience, and the extraction and use of valuable information. At the same time, the public must remain confident about the safety of the system. As a strong industry participant, the Federal Reserve Banks and others must continue to foster innovation while promoting the security of payments from end-to-end amid rapidly changing technology and evolving threats.

To begin to address these issues, the governing body of Federal Reserve Bank payment services issued a public consultation paper in 2013 articulating desired outcomes for the future environment. The paper’s goal was to understand key areas where the U.S. payments system could become safer, more accessible, faster and more efficient for end users. It also took into consideration the Fed’s role in implementing these changes.

In the course of this work, the Chicago Reserve Bank continued to play a critical role. We worked closely with our many partners, actively led research efforts and collaborated with traditional and non-traditional payment participants regarding changes in the payment environment. The Chicago Fed also hosted another successful Payments Symposium in 2013, in which key industry leaders gathered to offer their perspectives on desired outcomes for the industry. The symposium has gained a reputation in recent years as the leading conference in the country for the payment industry. We look forward to hosting the fourteenth edition of this annual symposium in September of this year.

In summary, 2013 was the year of gaining input on the appropriate next steps for the Federal Reserve Banks and what their role should be in improving the payment system for the digital age. Although we are still in the process of mapping out the future, one thing we are certain about is that the Federal Reserve, including the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, will continue to fulfill its century-long mission of improving the efficiency and accessibility of the nation’s payment system.

Contributing to the development of this essay were Kirstin Wells, vice president in the Bank’s Risk Management group; Mike Hoppe, vice president in the Customer Relations and Support Office (CRSO); and Ellen Bromagen, CRSO Executive President.

*As measured by the dollar value of money that is cleared and settled on ACH networks.

In December of 1913, President Woodrow Wilson signed legislation creating the Federal Reserve System. The new law called for the creation of between eight and 12 regional Reserve Banks that – together with the Board of Governors in Washington– would form the central bank of the United States.

Almost a year later, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago – along with the other 11 regional Reserve Banks – opened for business. It was November 16, 1914. One of the Bank’s original employees later described the scene: “After less than three weeks of preparation...some place to hang your hat and coat — a few desks and stools...the message from Washington [arrived], ‘All ready — get set’ and Governor McDougal’s happy smile and hearty handshake and then, ‘We’re off’ — the roar of flashlights to the click of the newspaper cameras...”1

While the Bank and its 41 employees were ready to carry out their appointed duties, exactly what these duties would be was to some extent unclear. Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act to furnish “an elastic currency” and provide for effective banking supervision, among other responsibilities. The Bank’s first annual report noted optimistically, if somewhat uncertainly, that the “various departments are now fully organized and equipped and in readiness for increased activities, whatever they may be.”

Since that time, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago staff members have contributed in many ways to the Fed’s role as the government’s fiscal agent, as a regulator of financial institutions, and as the overseer of the national payment system. The Fed also creates national monetary policy, carrying out an array of important jobs that affect the economy and the overall financial system.

On the pages that follow are a collection of nostalgic images from our past, simple reminders of “a century of service.”

1 Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 1919–1931, Among Ourselves, Chicago, Various Issues.

Some of the first leaders of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago gather to celebrate its opening on November 16, 1914. From left to right are Board of Directors Chairman Charles Henry Bosworth, Federal Reserve Agent and president of Chicago-based First National Bank; Charles R. McKay, Deputy Governor and manager of First National Bank; Board of Directors member W. F. McLallen; B. G. McCloud, Cashier and Assistant Secretary of the Board; and Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Governor James B. McDougal. McDougal was the first head of the Chicago Fed and served from 1914 to 1934.

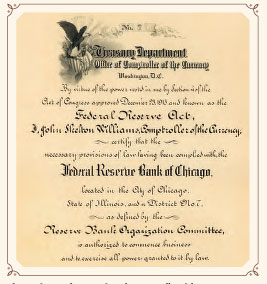

The certification document from the Comptroller of the Currency authorizing the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago to begin operations. The Chicago Fed opened for business on Monday, November 16, 1914.

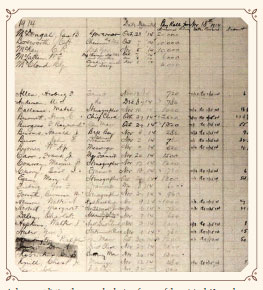

A document listing the annual salaries of some of the original 41 employees, from $20,000 for Governor James McDougal (the first head of the Bank) to $360 for bell boy John Lee.

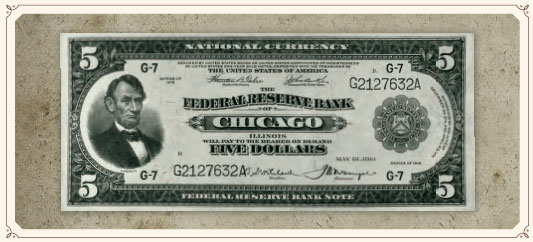

Federal Reserve notes were first issued in 1914 in $5, $10, $20, $50 and $100 denominations. They were redeemable in gold through 1933. There were also Federal Reserve Bank notes, which were not redeemable in gold. They debuted in 1915. They were backed by U.S. government securities held by individual Federal Reserve Banks. This $5 bill from the 1918 series includes the signature of the first head of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Governor James B. McDougal.

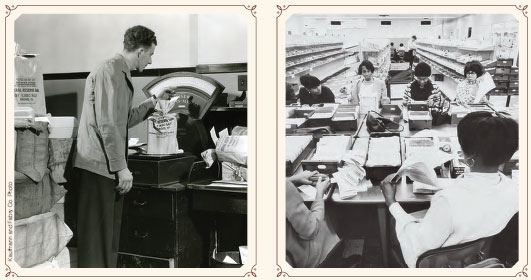

Currency processing underway in individual work stations.

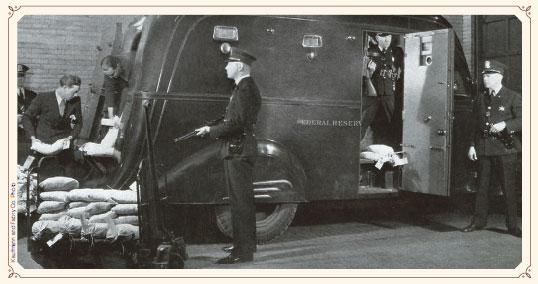

Security officers stand watch over the loading of a Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago armored truck.

A group of security officers practice in the firing range while a supervisor keeps track of time.

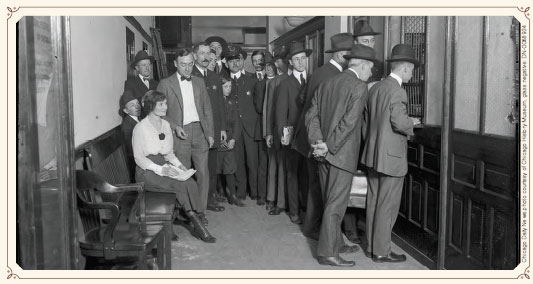

Customers line up to buy Liberty Bonds in 1917 on the second floor of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s Rector Building location on West Monroe Street. Chicago Fed operations were carried out at multiple downtown locations before completion of the Bank’s headquarters building in 1922.

Employees in the Bond Department examine and record individual securities.

A worker weighs bags of bonds.

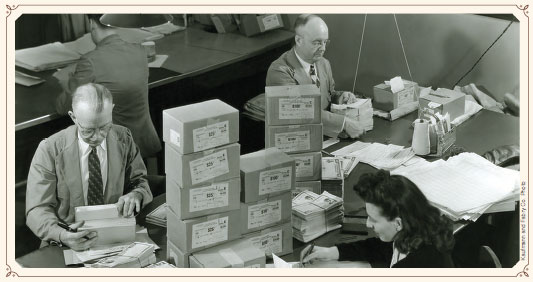

Employees hard at work in the check-processing department in 1987.

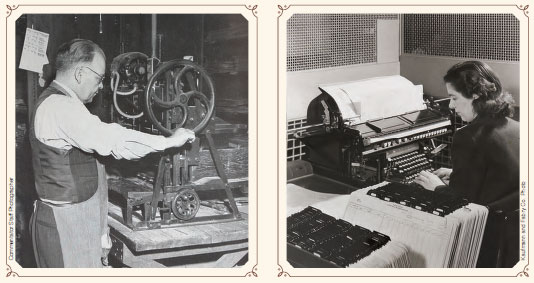

Fred Hager works at a book-binding machine in 1947. The machine was located in the Bank’s Bindery and Old Records Department.

A staff member types information pertaining to fiscal agency accounts and records into a special heavy-duty typewriter.

The cast of an employee theatrical production.

The Chicago Fed softball team started practice in late March in 1949 to prepare for the May 10 opening game. The team played in the Financial League.

Currency Department staff members and their families pose for a portrait during a picnic in 1920.

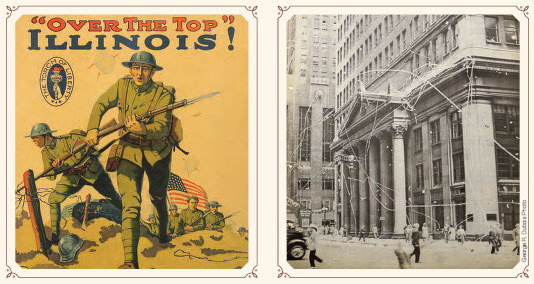

Created during World War I, this poster focuses on Illinois and advocates the purchase of War Savings Stamps, encouraging state residents to invest 10 percent of their income to help finance the war effort. The Chicago Fed was actively involved in war finance efforts.

The front of the Chicago Fed festooned in ticker tape during the joyous celebration that spread throughout downtown and lasted until dawn after the announcement of the end of World War II.

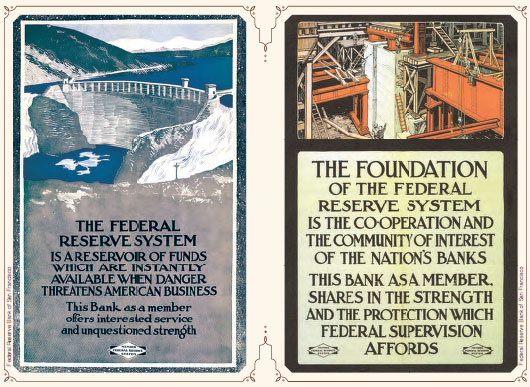

These posters date from the mid-1920s and were intended for display by member banks, possibly including those supervised by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Low bank membership was a concern for the Federal Reserve System in its early years, and there was even a joint Congressional hearing on the subject in 1926. These posters, with their images of strength and stability, were most likely intended to reassure the public and foster confidence in member banks. By doing that, they also likely fostered confidence in the Federal Reserve System.

More Information on Our History

If you would like to learn more about the history of the Federal Reserve System, a new website has been created at www.federalreservehistory.org. Essays, pictures and videos are available on the first 100 years, as are links to additional educational resources. For more information about the history of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the site to visit is www.chicagofed.org, which features background about the early days of the bank and its operations over the years.