The following publication has been lightly reedited for spelling, grammar, and style to provide better searchability and an improved reading experience. No substantive changes impacting the data, analysis, or conclusions have been made. A PDF of the originally published version is available here.

In recent years much attention has been devoted to the issue of racial discrimination in the home mortgage lending market. This interest has been fostered by the release of mortgage lending data under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1977 (HMDA). This act, which required depository institutions to disclose mortgage originations in metropolitan areas by census tract, was amended in 1989 to require lenders to report the disposition of every mortgage loan application, along with the loan amount and the race or national origin and annual income of each applicant. Analysis of the raw data contained in the annual HMDA data releases shows that there are persistent disparities in denial rates between White and minority applicants. Figure 1 reports HMDA denial rates by ethnicity for home purchases involving government-backed or guaranteed mortgages and conventional mortgages. As this table shows, denial rates for Black and Hispanic applicants were appreciably higher than those for White applicants in each year studied.

1. Loan denial rates

| Government-backed loans | Conventional loans | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicant | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 |

| (percent) | (percent) | |||||||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 22.5 | 22.1 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 22.4 | 27.3 | 26.6 | 27.8 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 12.8 | 12.5 | 13.5 | 11.7 | 12.9 | 15.0 | 15.3 | 14.6 |

| Black | 26.3 | 26.4 | 23.8 | 22.2 | 33.9 | 37.6 | 35.9 | 34.0 |

| Hispanic | 18.4 | 18.9 | 18.5 | 14.6 | 21.4 | 26.6 | 27.3 | 25.1 |

| White | 12.1 | 16.3 | 12.8 | 11.8 | 14.4 | 17.3 | 15.9 | 15.3 |

| Other | 18.4 | 16.3 | 16.0 | 17.8 | 19.0 | 19.9 | 21.0 | 23.1 |

| Joint (White/Minority) | 14.1 | 15.9 | 14.8 | 14.7 | 14.9 | 17.5 | 17.6 | 17.3 |

The persistence of these disparate rejection rates has led many industry critics to accuse banks and other mortgage lenders of engaging in discriminatory lending practices. However, HMDA data taken in isolation cannot shed much light into the question of discriminatory lending practices. This is because the HMDA releases do not provide other information crucial to the credit-granting decision, such as the loan applicant’s credit history, net worth and general financial condition, and employment history.

In response to this weakness in the raw HMDA data, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston conducted a study of mortgage denial rates in the Boston metropolitan area based on a much wider range of data.1 Using a sample of applications from the 1990 Boston metropolitan area HMDA files, Fed economists augmented the HMDA data with detailed information on applicants’ financial condition, credit history, personal characteristics, and the unemployment rate in the industries in which applicants were employed. They then estimated the probability of a particular mortgage loan application being denied.

Even with the addition of this information, race still appeared to have a statistically significant effect on the probability of being denied. When other factors were held constant, the rejection rate for Black and Hispanic applicants was about 1.6 times that for White applicants. Despite the interesting insights provided by the Boston Fed analysis, some have challenged its conclusions, questioning both the reliability of the data and the underlying empirical model.2 Given these concerns, the robustness of the study’s results remains an open question. However, while the Boston study has been criticized, it represents the first rigorous study of the question of discrimination in the loan approval decision.

This Chicago Fed Letter reports the results of a recent Chicago Fed study reexamining the role of race in the mortgage loan approval process.3 We began by carefully verifying and validating the data used in the Boston study. Then, unlike the Boston study, we analyzed the data using a model that tapped interaction effects among variables, examining approval probabilities for various subsets of applicants. While the Boston study found that Boston-area minority applicants were more likely to be rejected than White applicants with similar characteristics, our study indicated that this was the case only for applicants at the margins of creditworthiness. Marginal Black and Hispanic applicants appeared to be held to higher quantitative standards on such factors as credit history and debt ratios than were similarly situated marginal White applicants.

The cultural affinity and thicker file hypotheses

Despite the existence of legislation outlawing the use of irrelevant factors such as race and sex in mortgage lending decisions, lenders might still use these noneconomic facts as signals of whether to obtain additional information on marginal borrowers. Such information could ultimately influence the credit approval decision. One recent hypothesis suggests that a lack of “cultural affinity” between White loan officers and minority applicants reduces the reliability and accuracy of the loan officers’ subjective evaluations, as a result of which White banks have more demanding approval standards for Black and Hispanic borrowers.4 According to this hypothesis, if the marginal cost to White lenders of obtaining additional credit information on White borrowers is lower than that associated with minority borrowers, then White loan officers will rely more heavily on (inexpensive) objective loan application information for their minority applicants than for their White applicants. As a result, White applicants with marginal objective indicators of creditworthiness will be more likely to be approved than minority applicants with identical marginal credit records, because the White applicants will have additional subjective information supporting their case.

A somewhat similar hypothesis addresses the so-called thicker file phenomenon. Accepted marginal White mortgage applicants often have thicker loan application files than rejected marginal minorities. The common presumption is that White applicants receive special counseling or extra coaching by sympathetic White loan officers, while minority applicants do not. The cultural affinity and thicker file hypotheses both predict similar outcomes; they differ in that the cultural affinity hypothesis does not necessarily imply that White applicants receive special counseling and coaching or even have thicker application files than minorities.

The Chicago Fed study tested the cultural affinity hypothesis by examining whether loan officers perceive objective information such as credit history and leverage ratios differently for minority applicants than for White applicants. In addition, using a measure of applicants’ prior credit market experience, the study examined the thicker file hypothesis. Our results provided support for the cultural affinity hypothesis but not the thicker file hypothesis.

Our data and statistical model

To correct for data errors and missing values in the initial sample used in the Boston study, we adopted an extended version of the criteria developed by Carr and Megbolugbe.5 Our final sample contained 1,991 observations: 1,726 approvals and 265 rejections. The overall characteristics of this subsample mirrored that of the original data set.

Our statistical analysis used a standard logistic or logit regression model in which the lender’s loan approval decision is determined by a comprehensive set of borrower characteristics. The model predicts the probability that a mortgage applicant with a given set of characteristics will receive loan approval. The variables entered into the model were very similar to those in the Boston Fed study, including standard financial ratios such as housing expenses relative to monthly income, total debt obligations relative to monthly income, and other miscellaneous information such as marital status, employment status, and whether the loan applicant had a cosigner.

Race effects

The results of our study indicated that when the credit history of an applicant was classified as good (i.e., the applicant had no accounts 60 or more days past due), the approval probability for White applicants versus Black and Hispanic applicants was not appreciably different—96% for White applicants and 95% for Black and Hispanic applicants. On the other hand, when credit history was classified as bad (i.e., the applicant had one or more accounts 60 or more days past due), the difference in approval probability was 8 percentage points in favor of White applicants: White applicants’ approval probability was 90%, Black and Hispanics’ approval probability was 82%. These results suggest that for high-quality applicants, race was unimportant to lenders. It was the marginal minority applicant who was impacted by race.

It appears, then, that lenders did treat the objective loan application information of marginal Black and Hispanic applicants differently from that of marginal White applicants. In particular, credit history had a substantially greater impact on the probability of loan approval for marginal Black and Hispanic applicants than for marginal White applicants. While the approval probability dropped by about 13 percentage points for a minority applicant undergoing an adverse change in credit history, the probability dropped by only 5 percentage points for a White applicant undergoing a similar change.

These results provide strong support for the cultural affinity hypothesis. On the other hand, they provide no support for the thicker file hypothesis. The estimated direct effect of factors proxying for file thickness on the probability of approval was insignificant.

The study shows that race alone did not determine the differences in denial rates between applicants. To analyze the determinants more fully, however, one must consider the interaction between race and several other variables. In particular, the relationship between race and creditworthiness is key. The impact of race on the creditworthiness of a loan applicant will depend on the level of the applicant’s ratio of total monthly obligations to total monthly income. We computed the effect of race on creditworthiness within two levels of the debt obligation ratio—the lowest quartile and the third quartile. For applicants with bad credit histories, the effect of race on denial rates was small and statistically insignificant as long as the obligation-to-income ratio was low or favorable. However, when the ratio increased to an unfavorable level, the racial effect became larger and considerably significant, with Black and Hispanic applicants being adversely affected. For example, when the obligation-to-income ratio changed from a favorable 30% to an unfavorable 60%, the approval probability for marginal Black and Hispanic applicants decreased by 72.1 percentage points, compared to only a 24.5 percentage point reduction for marginal White applicants. Thus, as the ratio became less favorable, marginal White applicants appeared to be judged more creditworthy than were similarly situated marginal Black and Hispanic applicants. These findings lend additional support to the cultural affinity hypothesis.

Other results

The other findings reported in the study are consistent with traditional expectations. Specifically, increases in the ratio of total debt obligations to monthly income, evidence of prior public record defaults, self-employment, and having a less than favorable debt repayment history all lowered the probability of approval. So did being unmarried, being employed in an industry with a high probability of unemployment, and purchasing multifamily property. On the other hand, gender, the applicant’s number of dependents, and the racial or economic status of the neighborhood in which the property was located had no significant impact on the probability of approval. The finding that neighborhood racial or economic status had no impact on approval probability implies that the loan officers in the sample did not engage in the practice of redlining, i.e., denying loans on the basis of the racial or economic status of the neighborhood in which the property was located.

Implications

Overall, the study suggests that the marginal minority applicants in the sample were held to higher quantitative credit standards than were marginal White applicants. This is a more precise finding than that of the Boston Fed’s study. Our conclusion is implied by the behavior of the race variable under differing sets of conditioning information. Race was not a significant factor in the accept/reject decision for applicants with good credit profiles. However, it was very significant for those with bad credit histories, and a bad credit history, in turn, lowered the probability of approval for minority applicants much more than it did for White applicants. Similarly, race became an important factor only for those with high ratios of monthly debt to income. Minority applicants with high debt ratios were very much less likely to receive loan approval than similarly situated White applicants.

These findings are consistent with the existence of a cultural affinity between White lending officers and White applicants, and a cultural gap between White loan officers and marginal minority applicants. Bridging or closing this gap will require more research to identify the factors that determine the repayment patterns of marginal minority and nontraditional borrowers.

The search for evidence of racial discrimination in economic life is exceedingly difficult but can be made more manageable with the aid of statistical models. When used appropriately, these models can help regulators and researchers uncover discriminatory practices in mortgage lending. However, they should not be treated as replacements for sound judgment and inquiry. If one incorporates additional information into these models such as that included in bank underwriting policies and guidelines or other “omitted variables,” the models sometimes yield different results.6 Thus, in using statistical models in regulatory processes, policymakers face a classical problem: They must decide whether to expend additional resources to acquire more comprehensive information to build more customized models, when those models may add little value to the policymaking process.

Tracking Midwest manufacturing activity

Manufacturing output indexes (1987=100)

| April | Month ago | Year ago | |

| MMI | 138.6 | 141.6 | 132.2 |

| IP | 123.3 | 124.0 | 118.4 |

Motor vehicle production (millions, seasonally adj. annual rate)

| April | Month ago | Year ago | |

| Autos | 6.5 | 7.1 | 6.7 |

| Light trucks | 4.9 | 5.6 | 4.2 |

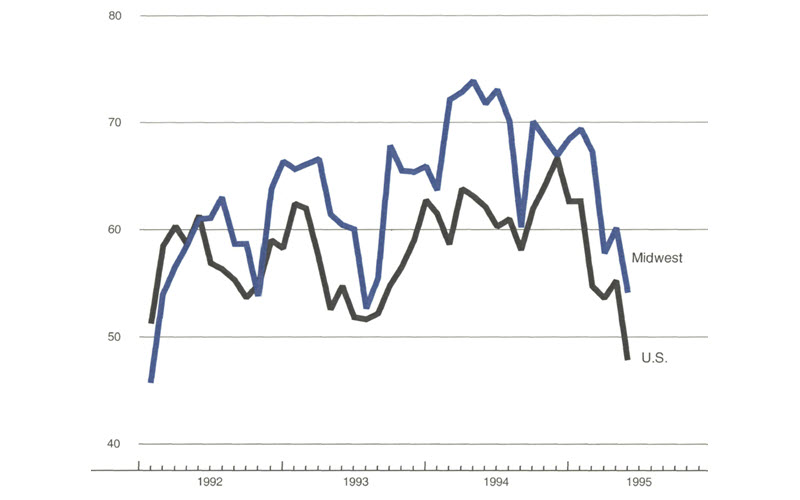

Purchasing managers’ surveys: net % reporting production growth

| May | Month ago | Year ago | |

| MW | 54.2 | 60.2 | 71.7 |

| U.S. | 47.9 | 55.3 | 62.2 |

Purchasing managers’ surveys (production index)

Sources: The Midwest Manufacturing Index (MMI) is a composite index of 15 industries based on monthly hours worked and kilowatt hours. IP represents the Federal Reserve Board industrial production index for the U.S. manufacturing sector. Autos and light trucks are measured in annualized units, using seasonal adjustments developed by the Board. The purchasing managers’ survey data for the Midwest are weighted averages of the seasonally adjusted production components from the Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee Purchasing Managers’ Association surveys, with assistance from Bishop Associates, Comerica, and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Inventory paring prompted retrenchment in Midwest industrial output growth in recent months. The composite index for purchasing managers’ surveys in Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee fell back significantly in March, April, and May. This indicator continued to depict positive growth in the manufacturing sector, but just barely. Even after its recent decline, the Midwest index remains in line with or stronger than its level during previous episodes of slowing growth in late 1991, mid-1992, and mid-1993.

Notes

1 Alicia H. Munnell, Lynne E. Browne, James McEneaney, and Geoffrey Tootell, “Mortgage lending in Boston: Interpreting the data,” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, working paper, 1992.

2 David K. Horne, “Evaluating the role of race in mortgage lending,” FDIC Banking Review, Vol. 7, Spring/Summer 1994, pp. 1-15, and Stan Liebowitz, “A study that deserves no credit,” The Wall Street Journal, September 1, 1993, p. Al 4.

3 William C. Hunter and Mary Beth Walker, “The cultural affinity hypothesis and mortgage lending decisions,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, working paper, 1995, forthcoming.

4 Charles W. Calomiris, Charles M. Kahn, and Stanley D. Longhofer, “Housing-finance intervention and private incentives: Helping minorities and the poor,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 26, August 1994, pp. 634-674.

5 James H. Carr and Isaac F. Megbolugbe, “The Federal Reserve Bank study on mortgage lending revisited,” Federal National Mortgage Association, Office of Housing Research, working paper, 1993.

6 See, for example, Mitchell Stengel and Dennis Glennon, “Evaluating statistical models of mortgage lending discrimination: A bank-specific analysis,” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Economic and Policy Analysis, working paper no. 95-3, May 1995.