Highlights from the "Post-Secondary Education Option" panel at the Kansas City Federal Reserve Community Development Conference

Earlier this month, the Kansas City Federal Reserve hosted a community development conference: “Exploring Prominent Issues in Financial Resiliency and Mobility in Low- and Moderate-Income (LMI) Communities.” The conference took a fresh look at a variety of issues that affect the financial wellbeing of LMI communities, including health care, housing, jobs, education and consumer finance. Around 200 people attended including community leaders, community development organizations and other non-profits, as well as representatives from the public sector, think tanks, and universities.

To further CDPS’ information sharing of how education and workforce development work together1, we are highlighting the presentations from the workshop entitled “Post-Secondary Education Options.”

“Post-secondary education” is defined broadly to include traditional university education and alternative options. The goal of this session with Leigh Anne Taylor Knight from ThinkShift, William Elliott from University of Kansas, and Bernard Franklin from Kansas State University, was to understand how post-secondary options and outcomes may be different for LMI populations. For example, what particular issues or limitations do they face? Is the return on investment for post-secondary education different for LMI versus non-LMI populations? Is anything fundamentally different about post-secondary education and training for this cohort?

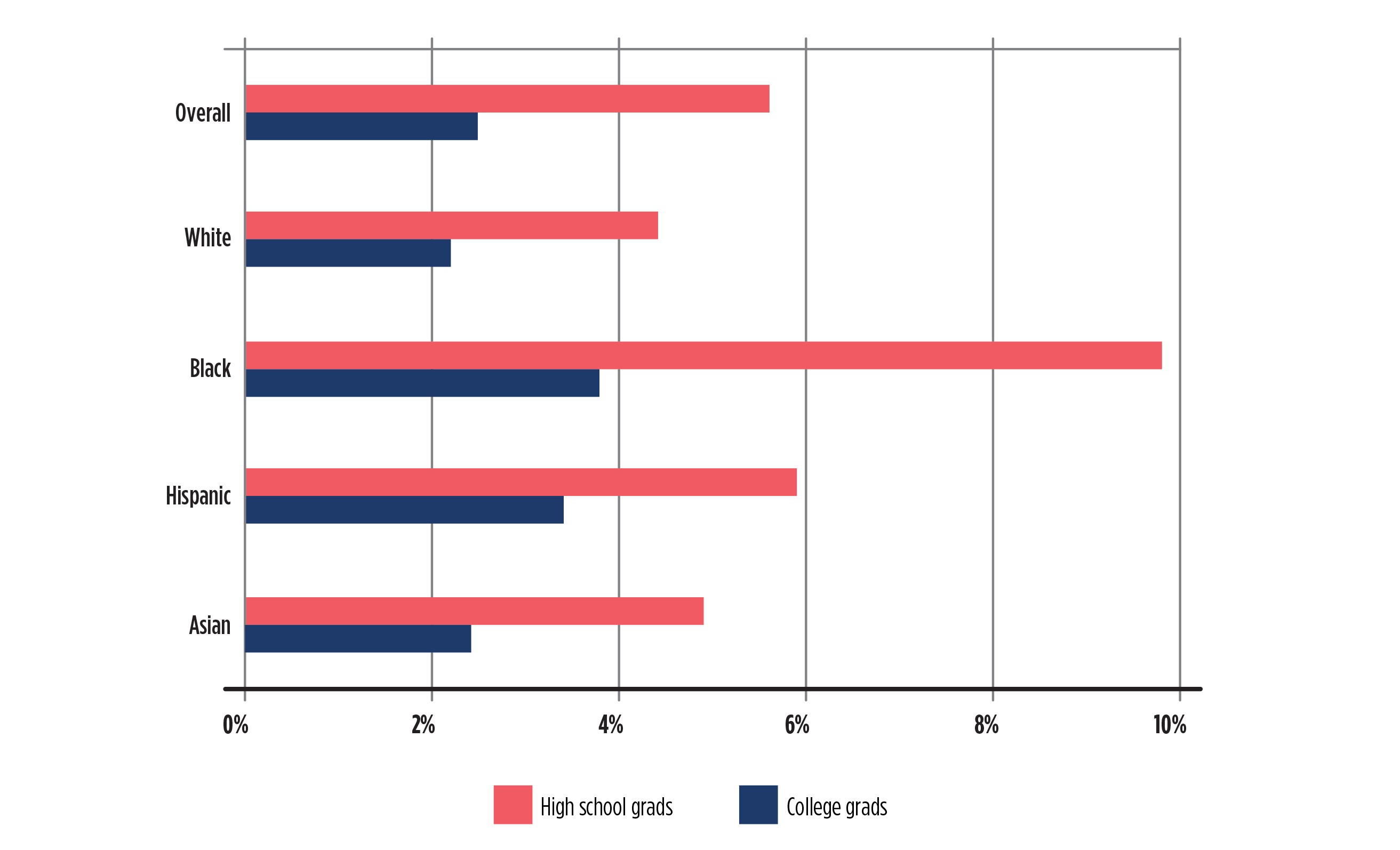

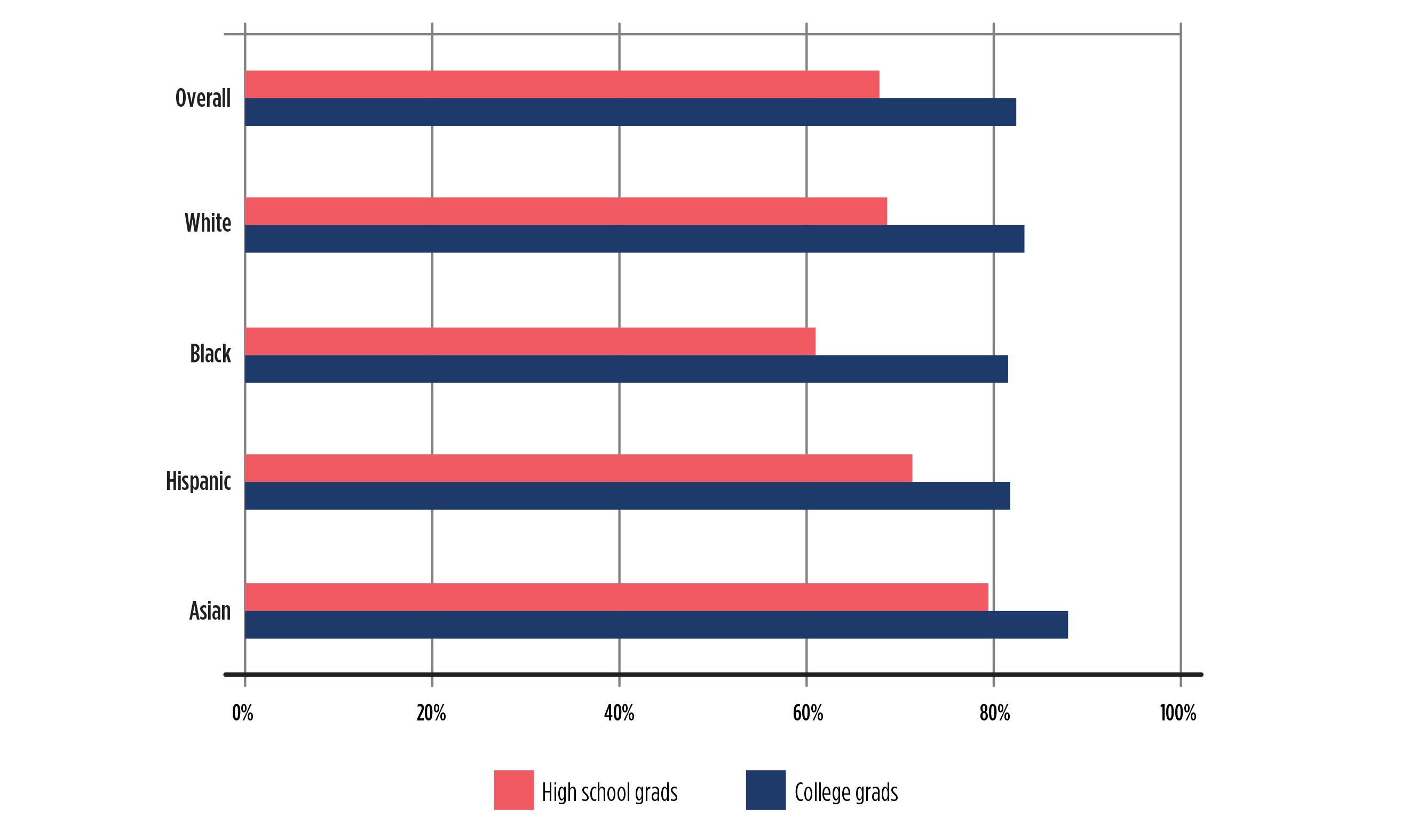

Dr. Leigh Anne Taylor Knight’s educational background includes serving as a K-12 assistant superintendent, advising learning institutions across the nation, and leading a bi-state consortium that provides tools for data-driven educational research to inform practice and policy. She noted that while college graduates are more likely to be employed and earn more money (see Chart 1 & Chart 2 below), a student’s particular course of study (major, principally) also impacts his or her return on investment.

1. High school graduates are more likely to be unemployed

2. College graduates are more likely to have jobs — percent of population that's employed

Notes: Age 25-64; median weekly wages; figures for blacks include Black-Hispanic. Figures for Asians include Asian-Hispanics.

Dr. Taylor Knight noted that chemical engineers made $70,000 annually as noted by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, February 2016 Survey (other STEM majors had high starting salaries too), while majors in religion and theology that made under $30,000 annually, based on the same survey. Furthermore, she explained that a degree does not necessarily lead to a career in a related field, meaning that many college graduates get jobs in fields unrelated to their major. Dr. Taylor Knight further explained that companies are beginning to work with schools to create curricula for certain jobs that students can fill after graduation.

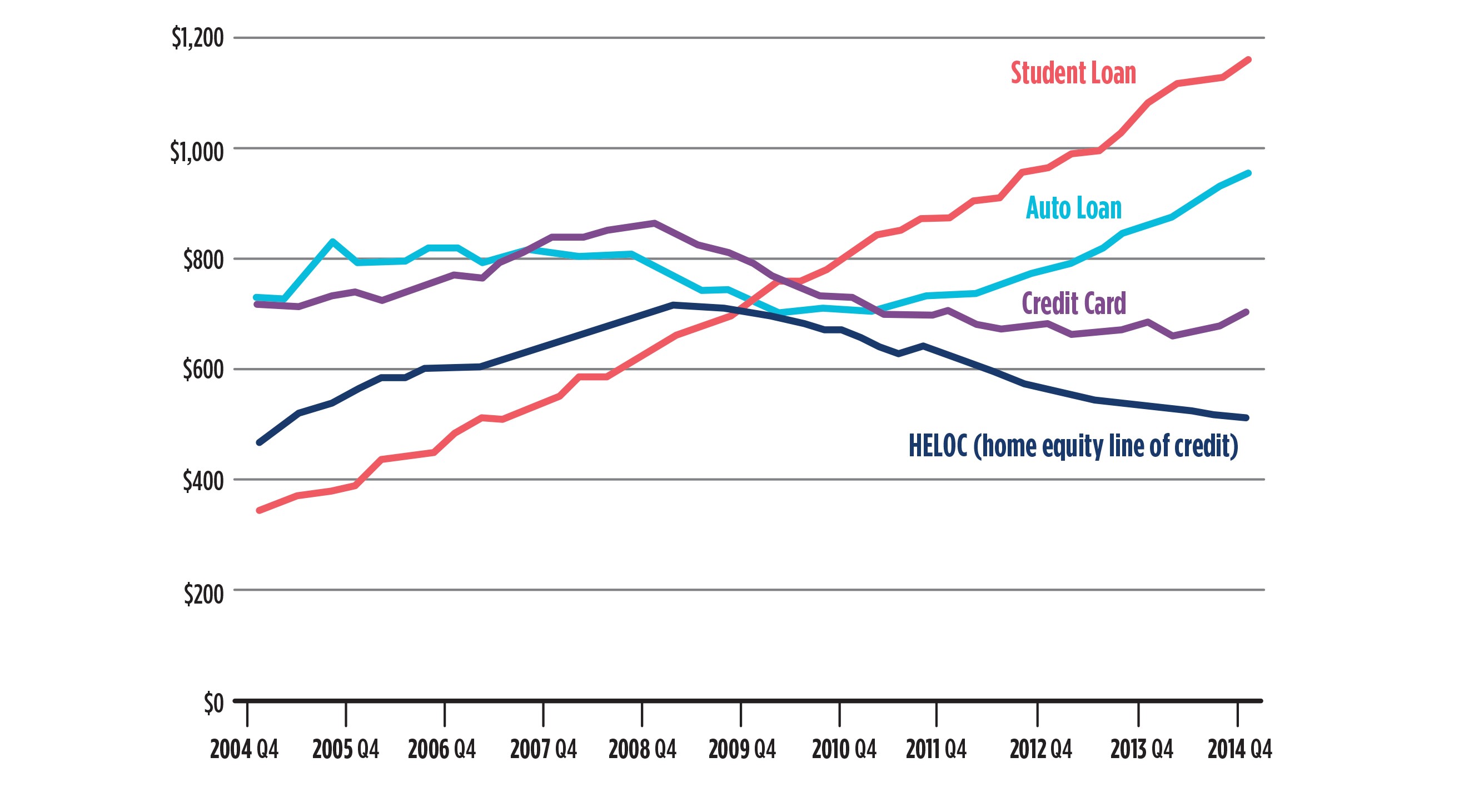

Dr. William Elliott furthered the conversation by discussing student debt and the life-long effects it can have on people, especially since students rely more heavily on loans today than ever before. Student debt burdens preclude or forestall major financial decisions, including: housing, saving for the future, and starting businesses. As illustrated by the chart below, student debt is the highest among the four categories of nonmortgage debt and it is steadily increasing.

3. Nonmortgage balances in millions of dollars

Dr. Elliott suggested solution for student debt burdens is, Children’s Savings Accounts (CSAs) along with a Promise Program because together they are, “creating an asset empowered path to the American dream.” (An example of a promise program is the Kalamazoo Promise: Work hard in school. Graduate! Earn a Promise Scholarship. Be successful in life!)

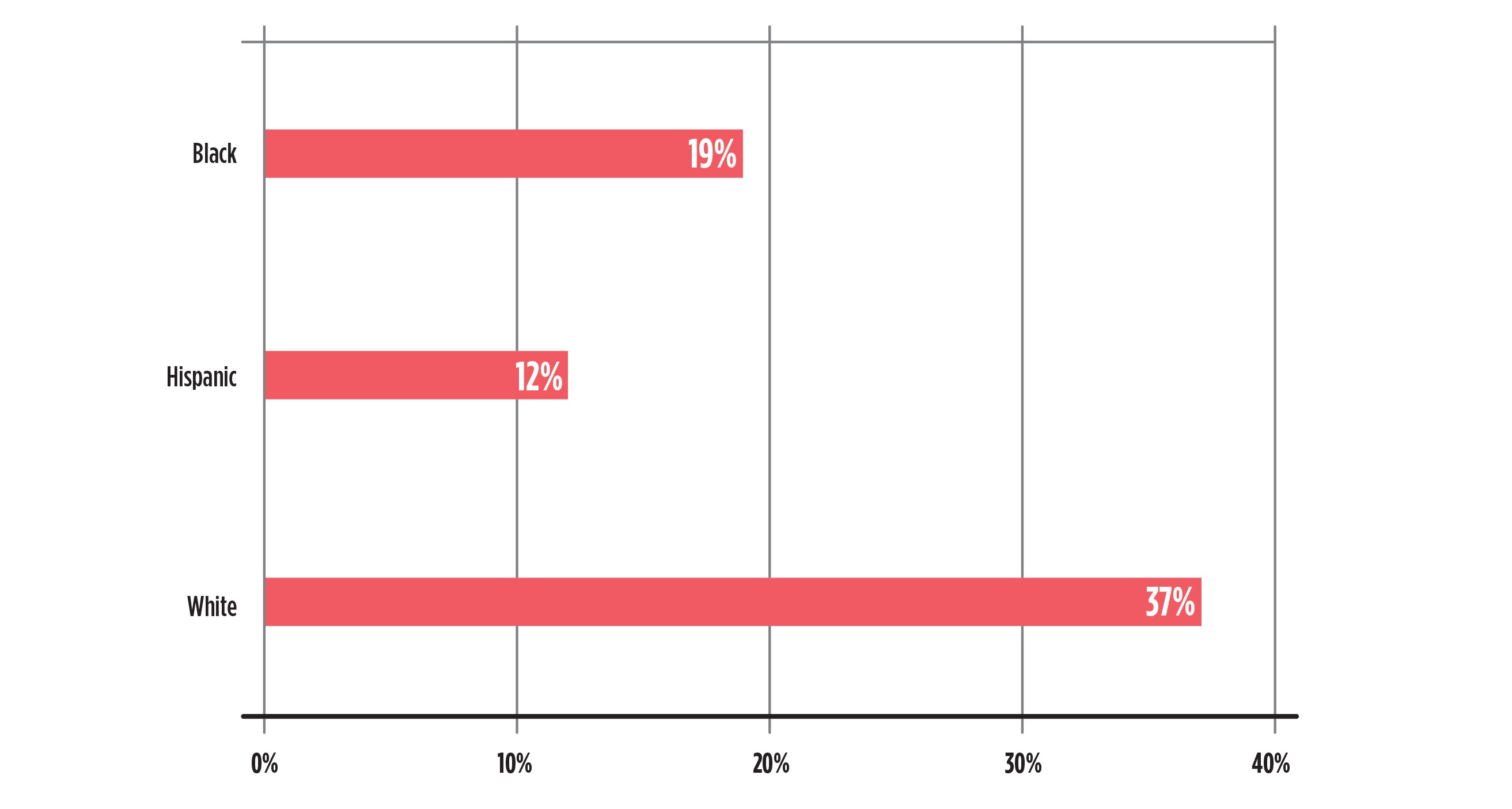

While CSAs could potentially be a long-term solution, they will only help the students who are currently too young to even think about college. Therefore, a short-term solution is also needed. He suggested a bailout policy: “Less Debt, More Equity: Lowering Student Debt While Closing the Black-White Wealth Gap.” Dr. Elliott argued that a progressive student bailout policy would dramatically reduce the racial wealth gap among low-wealth households. Furthermore, eliminating student debt among those making $50,000 or below reduces the black-white wealth disparity by nearly 37 percent among low-wealth households, and a policy that eliminates debt among those making $25,000 or less reduces the black-white wealth gap by over percent.

Dr. Bernard Franklin wrapped up the panel by describing a problem that exists throughout higher education: preparing students for a future we cannot clearly foresee. Many commonly understood job descriptions today did not exist even in the 1990s. This uncertainty, along with lower rates of enrollment that he projected after 2020, will likely cause institutions that rely on tuition dollars to change their financial structure, leading to increasing tuition rates above inflation rates (that has already happened at many institutions). Online education offerings may also proliferate due to their inherently lower cost structure, but online education may have negative implications that we cannot predict at this time.

The rest of Dr. Franklin’s presentation focused on issues of race and ethnicity in education. As indicated by the chart below, degree attainments for the black and Hispanic populations are significantly lower than for the white population.

4. Degree attainment by race/ethnicity — percent between the ages of 25 and 29 with a college degree

Dr. Franklin also stated that only one in 10 low-income students complete college, leaving most saddled with debt but no degree. He went into detail describing how those populations do not get the education they need to succeed in life. Dr. Franklin referenced a program that helps both low-income and first-generation students increase college access called The Kansas State College Advising Corps. This program works in public high schools by placing “near-peers,” recent college graduates, in public high schools to provide the support that students need. This program is designed to help low-income and first-generation college students access (and complete) post-secondary education.

This brief summary of one panel identifies issues impacting LMI students aspiring to achieve a college education, and potential policy interventions to help the LMI population succeed. We plan to post blogs from some panelists that can offer additional detail and insights. To see the activity and conversations started by the panel and conference, please check out #strongcommunities16 on Twitter.

Footnotes

1 Two ProfitWise News and Views articles that discuss the topic: "Community Colleges and Industry: How Partnerships Address the Skills Gap" and "From Classroom to Career: An Overview of Current Workforce Development Trends, Issues and Initiative."