Interstate Income Convergence and Development Policy

These days, there is some concern over rising income inequality among workers and households in the United States, especially slow wage growth at the bottom of the income distribution. In contrast, from a longer-term perspective, America’s general experience with household well-being has been strongly positive—both across time and geographically. Over the 20th century, household incomes have risen many times over. Reports from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas document American progress in tangible living standards, such as gains in homeownership, rising income, shorter work weeks, and rising life expectancy.

In its 2005 Annual Report, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland takes a geographic perspective on economic progress. Here again, a longer-term perspective is very positive. Against the backdrop of rising national standards of living, the report finds increasing geographic income equality rather than inequality. In particular, average incomes across U.S. multi-state regions, and among states in general, have been profoundly converging rather than diverging.

The causes and mechanisms of this income convergence are worth exploring in identifying possible lessons and directions for economic development policy today. What factors and policies can keep states and regions out in front of the race for economic well being? States in the Midwest are especially concerned that they are falling behind economic growth and well-being of some other states in the South and West.

In its methodological approach, the Cleveland Fed analysis attempts to explain the lack of full convergence of interstate per capita income since 1934. Neoclassical economic theory predicts that full economic convergence will take place in a flexible market economy, such as the U.S. economy. If, as we generally believe to be the case in the U.S., states share the same technologies in production, and if factors of production (labor and capital) are mobile across regions, then wages and household incomes should converge. Such convergence takes place over time as workers migrate toward better jobs and income or as capital investment follows greater returns in lower-cost regions. (There are other variants of the economy’s flexibility that achieve the same result).

As the Cleveland Fed’s chart below shows, in the U.S., state per capita income has mostly converged since 1930—it has converged from a standard deviation of around 0.4 to a mostly flat standard deviation of 0.15 since the late 1980s. Much of this convergence reflects rapid growth and economic progress in the formerly underdeveloped southern states. In the South, major public investments in education and roads, accompanied by private investments by manufacturing companies and more recently by services, have brought up incomes close to national norms and eliminated many areas in dire poverty.

1. Income convergence

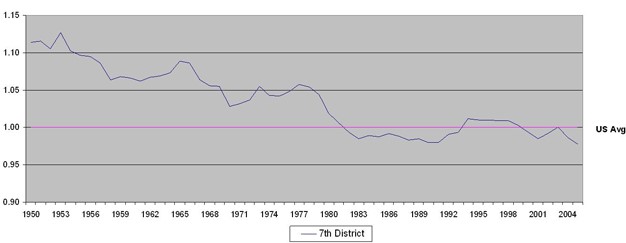

States of the Seventh Federal Reserve District have historically enjoyed average incomes above the nation. However, in recent years, per capita income growth in the District has lagged the nation’s average. (The Midwest web page allows visitors to build customized charts of state personal income). The chart below illustrates that District states’ per capita income remained at more than 10 percent above the nation’s average during the early 1950s. By the late 1970s, relative income had converged to levels only 5 percent above the nation. A more preciptious decline took place from the late 1970s to 1983 when relative income first fell below the national average, and remained there throughout the 1980s. The more prosperous times of the 1990s lifted the region’s incomes above parity for awhile only to fall below once again in the current decade.

As the second chart below reveals, all five states of the Seventh District have experienced relative declines since 1969.

2. Per capita income relative to the U.S. average

3. Per capita personal income relative to the U.S. average

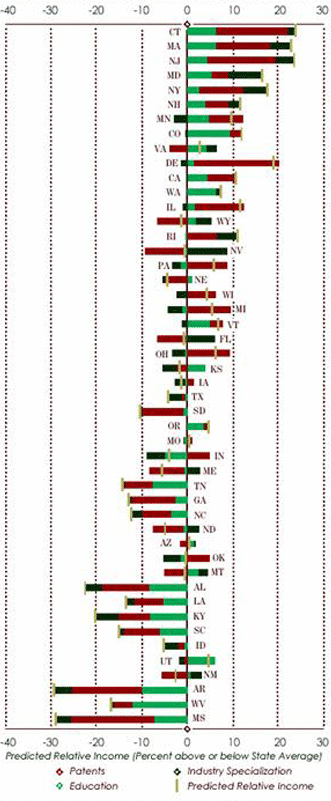

Since full convergence of state incomes has not taken place, it may be the case that public policies are feasible to push a state’s per capita income above or below average. The Cleveland Fed’s statistical model comes up with fairly strong evidence in identifying variables that explain or at least correlate well with why states fail to fully converge with the national average. The strongest explanatory variable is “utility patents”—a proxy or general stand-in for states’ innovation and entrepreneurial activity. Apparently, local innovation can keep incomes high in a region as new firms (and high paying jobs) are spawned or through some other mechanisms.

The second strongest explanatory variable explaining lack of full convergence is differences in educational attainment among the states’ work forces as measured by high school and college education attainment. Presumably, while U.S. workers are mobile in moving to other states in search of higher wages, this migration mechanism is imperfect or slow to adjust. Accordingly, some economic returns from public investment in college education may accrue to the students’ home region (and therefore income convergence is incomplete). Education is also considered to be complementary with “patents” or innovation in economic growth because a highly educated population can more easily learn and adapt new technologies.

The important third variable is “industry specialization.” Places with concentrations of manufacturing had higher incomes early on, but this has since tended to dampen income growth over time (and has tended to do so persistently). Presumably, a region’s workers cannot or do not adjust quickly (e.g., move away or retrain) to the negative shocks that have affected such industry sectors.

What can we take away from such an analysis? The Cleveland Fed intends this initial research to be directional rather than prescriptive. That is, it offers guidance and direction for further research that is needed to identify viable and specific public policies.

In some sense, the research findings are also corroborative. That is, the findings are very much in the mainstream of current economic development policy discussion. How to innovate? How to educate? Which policies will continue to enhance growth? And ultimately, which particular policies toward educational attainment and entrepreneurship are effective and cost-effective?

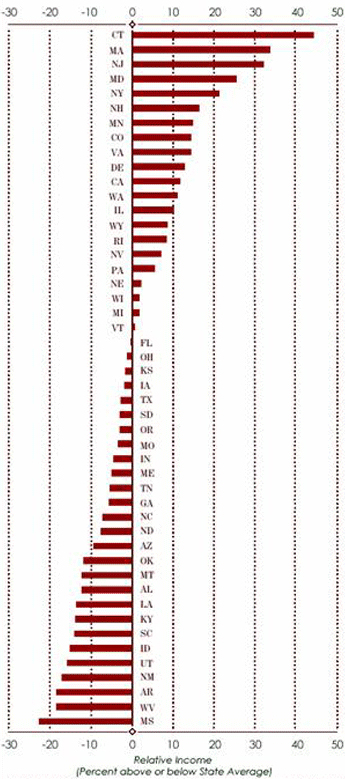

What do the findings have to say specifically about Seventh District states and other Midwest industrial states? The side-by-side charts below illustrate the findings for each state. The left-hand chart lists the actual per capita incomes of each state in 2004 in relation to the national average. The right-hand chart lines up this same listing of states with the Cleveland Fed’s model of predicted per capita income. The particular contribution of each explanatory factor to the prediction—innovation, education, and industry mix—are also illustrated.

4. State relative incomes in 2004

5. Predicted impact of key factors on 2004 state incomes

The Cleveland Fed analysis predicts Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin to have higher per capita incomes than they actually do have in 2004. (Iowa and Indiana are right on par.) Predictions that are stronger than actual for these Midwest industrial states derive from their high research and patenting activities.

Why, then, are Midwest states lagging in their incomes despite their strong innovative traditions? The possible explanations are thus far elusive. It may be that the model’s enumerated patents are mismeasuring (overcounting) actual innovation taking place in the Midwest region, since patents are sometimes assigned to the headquarters of a firm in a region, even though the innovative activity takes place elsewhere. In an increasingly global economy, with large multinational companies, this data problem may be worsening over time.

Another possibility is that patents in the Midwest’s particular industries have lower economic returns lately as compared with patents in those industries (e.g., microchips or software) that are more specialized in other states and regions.

Yet another possibility has been most intriguing to Midwest leaders in economic development thought and policy. Is it the case that some other feature of Midwest behavior or policy is failing to commercialize research innovations that are taking place or available here?

Again, the possibilities are myriad. Among them, some researchers have pointed to superior mechanisms that have been crafted in successful regions, including Massachusetts, North Carolina, and California, whose universities have been successful in transferring research and development from the laboratory to commercial enterprise. The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland will take a closer look at this proposition during its November conference on the university’s role in technology transfer. At its October 30 conference, the Chicago Fed will also be taking up this issue as it investigates several possible roles that the university might take in regional economic development.