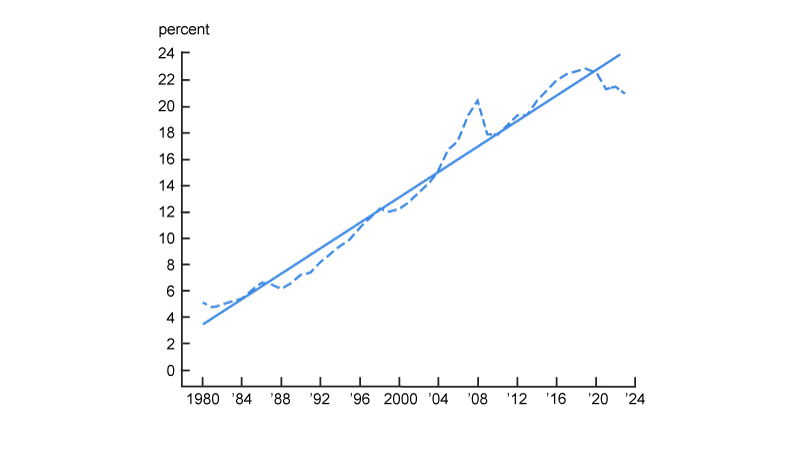

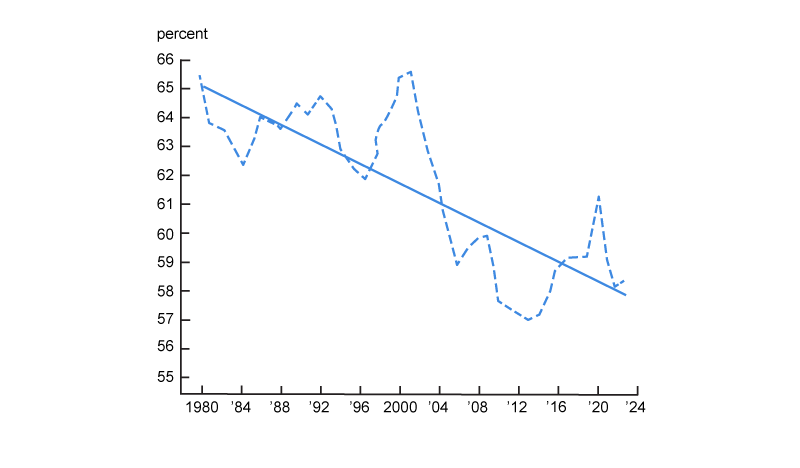

Public corporations account for about half of private employment in the United States.1 These large corporations have undergone radical changes in their ownership structure over the past several decades.2 Figure 1 illustrates the changes—total block institutional ownership, defined as the total share of equity owned by all institutional investors that own at least 5% of the shares for public firms, on average increased fourfold from 1980 to 2023. As a result, the block institutional shareholders, on average, held over 20% of the equity shares of U.S. public corporations by the end of the period. In parallel, figure 1 (panel B) shows that the labor share, as measured by the ratio of total compensation for employees to output, exhibited a declining trend.

1. Trends in institutional ownership concentration of public firms and labor share, 1980–2023

A. Total block institutional ownership

B. Labor share

Sources: Institutional ownership is from Thomson Reuters 13F filings data, and the labor share is from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Is there a connection between these two trends? If so, what does it imply for the status of labor markets today and workers’ welfare in the macro economy? My collaborators, Antonio Falato, Daniel Gallego, Till von Wachter, and I explore these questions in our research using confidential micro data sets from the U.S. Census Bureau that span several decades. This rich data set, combined with a universal data set on U.S. public firm ownership by institutional investors, provides information on employment, payroll, earnings, and detailed ownership structure for over seven million business establishments and over nine million individual worker observations.

These representative administrative data sets allow us to track individual establishments and workers across different firms over time after changes in their firms’ ownership structure—which in turn allows us to explore the economic links between institutional ownership concentration, shareholder power, and workers’ labor market outcomes. I summarize our work in this Chicago Fed Letter.

The economic linkages

First, what is the link between concentration of institutional ownership, as measured by, e.g., total block institutional ownership in figure 1 and so-called “shareholder power?” Our hypothesis is that ownership concentration provides shareholders with increased “power” to achieve their goal—which we assume is maximizing shareholders’ value. Intuitively, when ownership is more concentrated, shareholders would have stronger incentives to spend resources to improve their returns (e.g., by suggesting different ways to management to run the business). Increased ownership concentration could also facilitate coordination among shareholders in achieving the goal of maximizing their returns. Thus, we argue that increases in ownership concentration improve shareholders’ overall power to maximize their value. We focus on external, institutional ownership (as opposed to insider3 or individual ownership), given that institutions’ incentives are well-aligned with maximizing shareholders’ returns, whereas individuals, especially managers of the firm, are more likely to have potentially conflicting goals concerning their own benefits. Among the institutions, those with motives to control the invested firms’ business would matter the most—i.e., “dedicated” or “activist” institutions as opposed to “indexers and “transient.”4 Viewed through these lenses, the rise in institutional ownership concentration suggests shareholder power in the U.S. has grown over recent decades.

Now turning to the link between shareholder power and workers’ labor market outcomes, we are motivated by the agency theory of the firm, which is based on conflicts between shareholders and workers (Jensen and Meckling, 1976), over allocation of firm resources. One can perhaps see this type of potential conflict in the Business Roundtable Statement on the Purpose of the Corporation (2019), for example. In this theory, “powerful” shareholders could affect workers’ labor market outcomes through two non-mutually exclusive channels. First, they can use their “power” to allocate more resources toward shareholders from workers. Second, they can monitor firm managers and discourage them from having a larger workforce and paying higher wages, which could benefit the managers at the expense of shareholders. In both cases, the presence of powerful shareholders hurts workers while improving shareholder returns.

Increases in institutional ownership concentration hurt employees

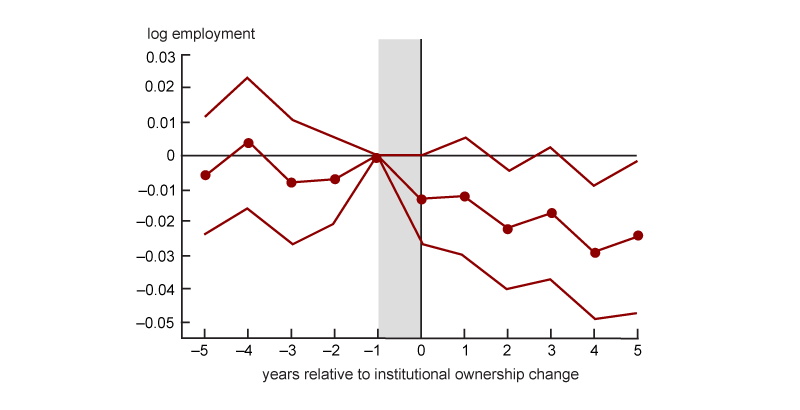

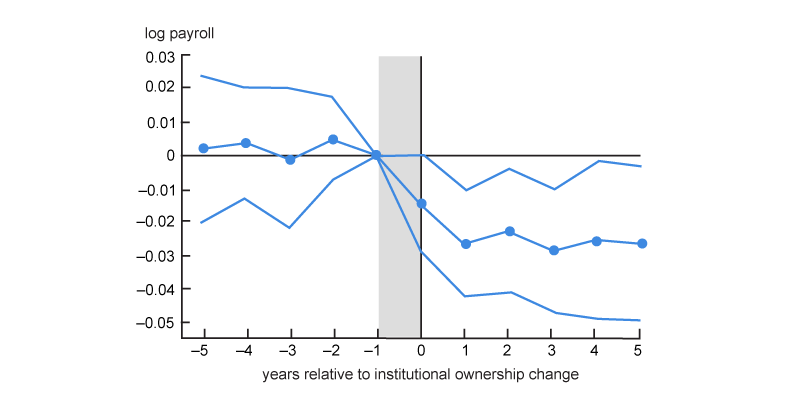

Motivated by the theory and using the Census data sets, we analyzed how increases in institutional ownership concentration affect the size of establishment-level workforces and individual-level labor earnings. We did so by following establishments and workers over time in an “event-study” framework.

In this framework, we form a sample of establishments or workers that experience an increase in total block institutional ownership of more than 5 percentage points within a year as our “treated” group—The idea is that the workers in these establishments face shareholders with increased power. These events may happen as new institutions build block ownership stakes in the firm, or institutions with previously minor stakes increase their stake above 5%. We assemble a “control” group of establishments or workers that also experience an increase in overall institutional ownership of more than 5 percentage points, but importantly, not total block institutional ownership.5 For example, the treated workers may experience a 10 percentage point increase in total block institutional ownership in a given year, while the control workers experience a 10 percentage point increase in overall institutional ownership in that year but their block institutional ownership remains the same. By comparing the outcomes for the treated and control groups, we net out any effects of the increased institutional ownership level, in an attempt to isolate the “pure” effects of institutional ownership concentration.

Figures 2 and 3 present the results of this analysis for establishments and workers, respectively. Figure 2 shows that establishment-level employment (panel A) and payroll (panel B) evolved similarly prior to the increases in ownership concentration (i.e., from years –5 through –1 on the x-axis). This result provides evidence that the treated and control groups’ outcomes would have evolved similarly had the changes in ownership concentration not occurred. After the increases in ownership concentration, however, treated establishments experience losses in employment and payroll relative to the control establishments. The estimates indicate that employment and payroll decrease by 2% to 2.5% as a result of the increased ownership concentration.

2. Establishment-level analysis

A. Effect on log employment

B. Effect on log payroll

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Thomson Reuters 13F filings data.

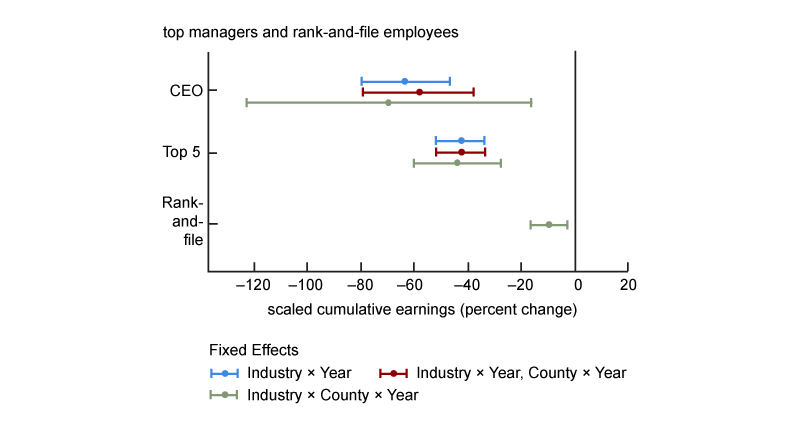

Turning to the worker-level results in figure 3, we examine heterogeneity in the impact on workers’ earnings by their rank within firms—chief executive officer or CEO (the highest-paid employee), the top five highest-paid employees, and the rest (called rank-and-file). In this analysis, the outcome variable is normalized cumulative earnings, defined as the sum of a given worker’s labor earnings from years zero through six, scaled by the average annual earnings of the worker over years –5 through –1. Thus, the variable captures six-year cumulative labor earnings of workers after the event, as a fraction of the average pre-event annual earnings.

3. Worker-level analysis

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Thomson Reuters 13F filings data.

The results show that the highest earners of treated firms (CEOs) lose 63% of their pre-event annual earnings over the six post-event years relative to the CEOs of control firms. The five highest earners, including the CEOs, of treated firms experience a 43% reduction in cumulative earnings, on average. In comparison, rank-and-file employees of the treated firm experience the smallest magnitude reduction in their cumulative earnings—10% of their pre-event annual earnings.

The results suggest that increases in concentration of institutional ownership, and thus shareholder power, are generally bad for firm employees, particularly for those in the highest pay ranks. Tying back to the economic linkages between shareholder power and workers’ labor market, we interpret the evidence in the following ways. First, powerful shareholders are able to allocate more resources (or rents) toward shareholders from highly paid employees, including top managers. This interpretation is consistent with the broad finding in the literature that firms’ sharing of economic rents with employees is more pronounced for higher-paid workers (see, e.g., Kline et al., 2019). Second, if managers have stronger preferences for keeping employment high and paying high wages (which could help maintain positive relationships with employees) than shareholders, more powerful institutional shareholders would like to reduce both employment and pay in an attempt to maximize their value. This could be one specific way for rents to reallocate to shareholders. Now, we examine this rent-sharing interpretation in more detail.

Reallocative employee losses

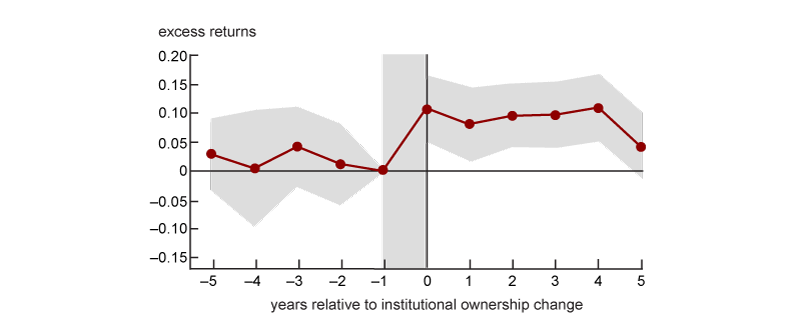

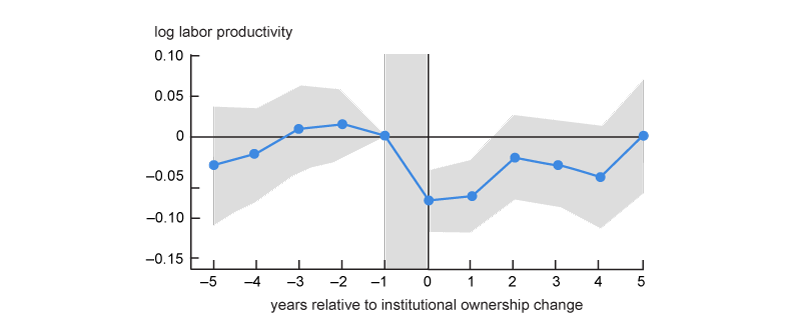

Who gains from the employee losses due to rising shareholder power? If powerful shareholders curb managers’ preference for large workforces and high employee wages, thereby reallocating rents away from employees, shareholders will benefit from it. To explore this prediction, we repeat our analysis with a measure of shareholder value, annualized excess stock returns, as the outcome. Panel A of figure 4 shows that increases in ownership concentration lead to increases in shareholder returns.

4. Effects on shareholder return and labor productivity

A. Effect on shareholder return

B. Effect on labor productivity

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Thomson Reuters 13F filings data, CRSP.

We further explore the impact of shareholder power on labor productivity of the firm by repeating our analysis with log of revenues per employee as the outcome. Panel B of figure 4 shows that increases in ownership concentration have a negative short-run effect on labor productivity but virtually no effect in the long run (i.e., from year two onward). Overall, the evidence indicates that shareholder power has largely a reallocative impact, as cuts in employment and wages take value away from workers toward shareholders without increasing firm productivity.

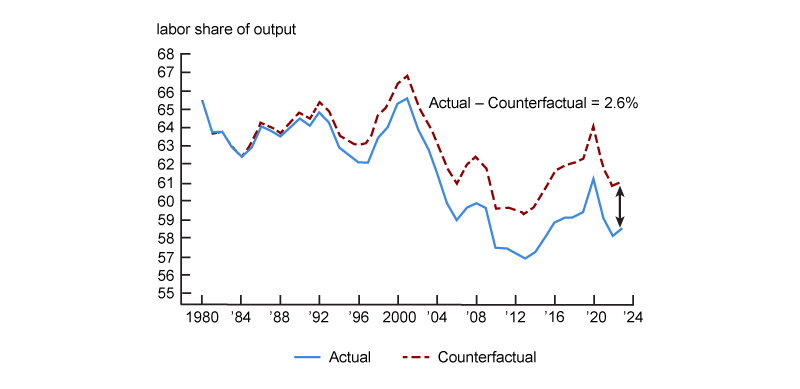

Implications for labor share

The public corporations we examine are important because they constitute about half of aggregate employment in the United States. Thus, the overall negative effects of increasing concentration of institutional ownership on public firm employees that we find may have a considerable impact on the labor share of income in the economy. To explore the macroeconomic implications of our micro evidence, we calculate how much of the decline in aggregate labor income we can explain with rising shareholder power.6 Our analysis produces estimates that suggest a 1 percentage point increase in total block institutional ownership is associated with a 0.17% reduction in payroll. Based on this relation, we calculate the implied time-series effect on the labor share, given the change in average total block ownership from 1980, the reference year, to a subsequent year. The results in figure 5 indicate that the rise in shareholder power explains about a 2.6 percentage point decline, which is 38% of the overall decline in total compensation relative to output, by the end of 2023.

5. Aggregate implications, 1980–2023

Source: Thomson Reuters 13F filings data, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Census Bureau.

These results may have implications for future developments for employment, wages, and even inflation—which are plausibly affected by workers’ relative power (e.g., Goodhart and Pradhan, 2020). In particular, if the declining concentration of institutional ownership that began in 2020 (see figure 1, left panel) continues, it implies that the declines in employment, wages, and the labor share may be reversed in the coming years due to increased worker power.

Conclusion

U.S. labor markets have experienced a pronounced transformation over the past several decades, with labor income lagging behind strong productivity and profit growth. The research described in this article sets forth an explanation for the trends based on the changing nature of public firms’ ownership structure. Motivated by the agency theory of the firm, which presumes conflicts of interest between shareholders and stakeholders, we hypothesize that increases in institutional ownership concentration reduce firms’ workforces and workers’ labor earnings. The evidence suggests that increases in ownership concentration, and shareholder power, lower businesses’ employment and payroll and workers’ long-term earnings, while raising shareholder value without influencing firms’ long-term productivity. Our evidence is important in light of the fact that concentrated ownership constituted more than 40% of the overall ownership by institutional investors as of 2023. In turn, institutional investors own, on average, more than half of the shares of U.S. public corporations, which account for about half of aggregate gross domestic product (GDP) and employment in the United States. Hence, the negative effects of institutional ownership concentration on employment and wages we document potentially influence a substantial fraction of establishments and employees. In future research, we will examine the impact of other types of ownership changes, including those for private firms, which have become more important in the past decade, on labor market outcomes of workers.

This article is based on joint research with Antonio Falato, Daniel Gallego, and Till von Wachter. I appreciate feedback from Daniel G. Sullivan and Leslie McGranahan and excellent research assistance from Joe Jourden. Any views expressed are those of the authors and not those of the U.S. Census Bureau or the Federal Reserve System. The Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board and Disclosure Avoidance Officers have reviewed this information product for unauthorized disclosure of confidential information and have approved the disclosure avoidance practices applied to this release. This research was performed at a Federal Statistical Research Data Center under FSRDC Project Number 1572 (CBDRB-FY20-P1572-R8820; FY22-P1572-R9381; FY23-P1572-R10474, R10819).

Notes

1 For example, in 2019 public firms in the Compustat database employed 81.7 million workers in total, representing 50% of the U.S. civilian labor force (of 163.5 million workers).

2 Our work in this area is ongoing and includes Falato et al. (2022).

3 “Insider ownership” typically means ownership of equity by all directors and officers of a firm. See, e.g., Fahlenbrach et al. (2009).

4 These classifications follow work by Bushee (1998). Transient institutions have high portfolio turnover and diversified portfolios, while dedicated institutions have low turnover and more concentrated portfolio holdings. Quasi-indexer institutions have low turnover but diversified holdings. Activist institutions are as classified by Grennan (2019) based on institutional investors that have engaged in shareholder activism campaigns.

5 Over the 1981–2014 sample period, the mean numbers of treatment and control events are 248 and 363 per year. As a comparison, the mean number of public firms with information on stock prices from Compustat is about 7,150 per year in the period.

6 For this aggregate analysis, we estimate the relation between total block institutional ownership and payroll on a representative sample of establishment-level Census data.